Privacy by Design is not a compliance exercise; it is an engineering discipline for building data protection into the core architecture of systems and products. It treats privacy as a fundamental requirement, not an optional feature bolted on before deployment.

The Problem: Privacy as a Technical Debt Catalyst

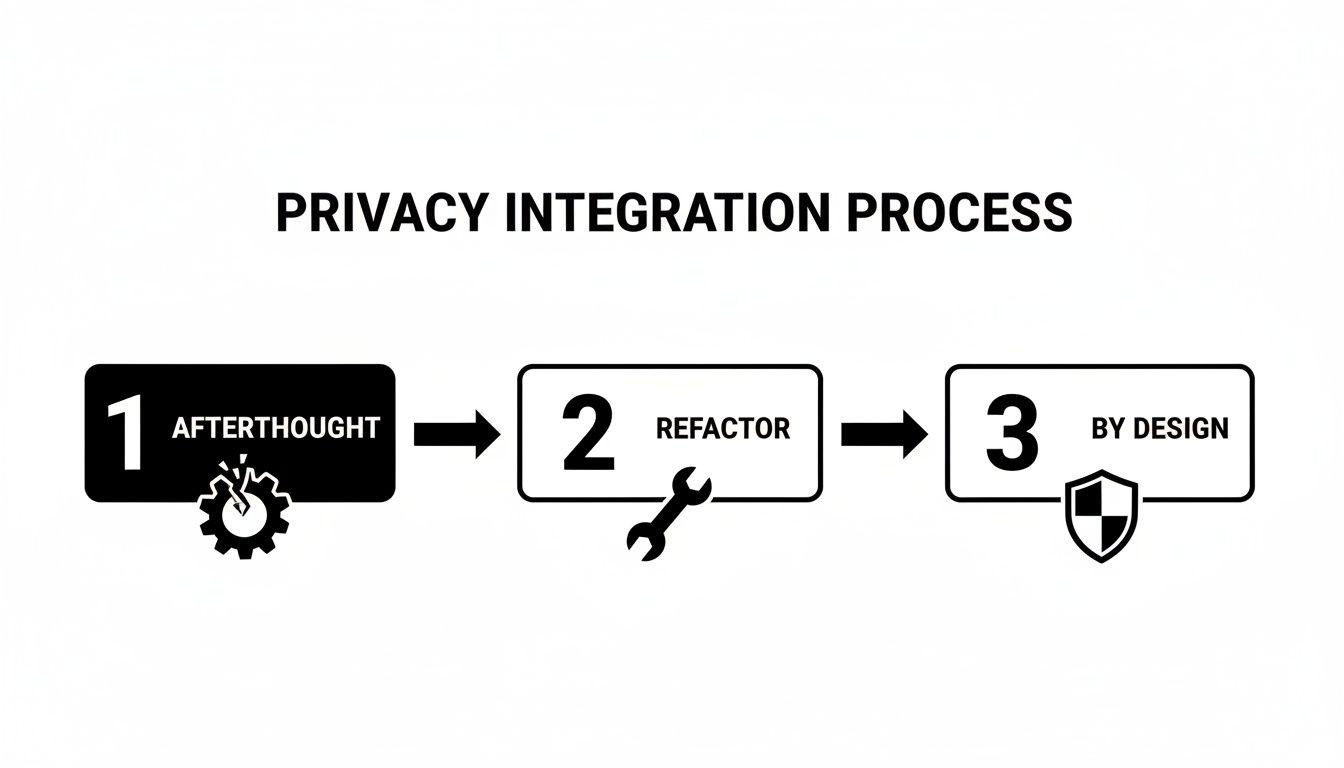

For many product teams, privacy is addressed as a final-stage compliance hurdle. This reactive approach is a primary source of technical debt. When privacy is an afterthought, engineering teams are forced into expensive refactoring, brittle integrations, and a perpetual struggle to add new features without breaking data handling rules. This is where vulnerabilities emerge and user trust is eroded.

Adopting Privacy by Design reframes the challenge. It shifts data protection from a legal concern to a core architectural principle. The premise is straightforward: robust privacy cannot be added later; it must be an integral part of the system’s design from inception.

This proactive stance creates significant architectural and business advantages:

- Reduces Technical Debt: Building privacy controls from the start avoids the costly, disruptive rework that plagues reactive teams.

- Enhances System Resilience: A system designed with privacy as a core concern is inherently more secure and robust—it is better engineered.

- Builds Customer Trust: Demonstrating a commitment to data protection is a powerful market differentiator that fosters loyalty.

- Simplifies Maintenance: When data handling is intentional and explicit, the entire system becomes easier to understand, maintain, and evolve.

The Financial Rationale for Proactive Privacy

Treating privacy as a low-priority task has tangible financial consequences. The global average cost of a data breach has reached $4.88 million per incident.

Crucially, organizations with mature Privacy by Design programs save an average of $1.5 million per breach compared to those with immature practices. This represents a 31% cost reduction. From this perspective, PbD is not a compliance expense but a strategic investment in financial resilience. You can find more insights on these breach cost savings at standardfusion.com.

Privacy is not about limiting features; it is about enabling trust through sound engineering. A system that protects user data by default is a well-architected, resilient system prepared for future challenges.

The Seven Foundational Principles

The concept of Privacy by Design is built on seven core principles articulated by Dr. Ann Cavoukian. For software engineers and architects, these are not abstract ideals but practical guidelines for system design and development workflows. They provide a clear framework for building products that respect users from the outset.

Translating Principles into Engineering Practice

| Principle | Core Concept | Practical Application in Software Development |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Proactive not Reactive; Preventative not Remedial | Anticipate and prevent privacy issues before they occur. | Conduct Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) during the design phase. Use threat modeling for data flows. |

| 2. Privacy as the Default Setting | No user action is required to protect privacy; it is built-in. | Default settings for data sharing are “off.” Data collection is minimized by default. Use opt-in for non-essential data processing. |

| 3. Privacy Embedded into Design | Privacy is a core component of the system, not an add-on. | Integrate privacy controls directly into the application’s architecture. Data encryption is a native feature, not a separate layer. |

| 4. Full Functionality—Positive-Sum, not Zero-Sum | Accommodate all legitimate interests without false trade-offs. | Design systems that deliver business value without compromising user privacy. Reject false dichotomies between features and data protection. |

| 5. End-to-End Security—Full Lifecycle Protection | Data is secured from collection to destruction. | Implement encryption in transit and at rest. Use secure data deletion methods. Enforce strict access controls throughout the data lifecycle. |

| 6. Visibility and Transparency—Keep it Open | Stakeholders understand what data is collected and for what purpose. | Provide clear, concise privacy policies. Implement user-facing dashboards for managing personal data and consent. |

| 7. Respect for User Privacy—Keep it User-Centric | The system architecture and design prioritize the user’s interests. | Design intuitive consent flows and easy-to-use data access/deletion request tools. Put the user in control of their data. |

These principles establish that privacy is not just another feature on the backlog. It is a fundamental quality metric for any well-engineered system.

Integrating Privacy into the Software Development Lifecycle

Effective Privacy by Design is not a one-off checklist but a continuous practice integrated into every stage of the software development lifecycle (SDLC). It requires a cultural shift from a reactive, “fix-it-later” mindset to a proactive engineering discipline where privacy is a core consideration.

This approach transforms abstract principles into concrete, daily habits for your engineering team, moving privacy from a costly afterthought to a strategic design principle.

Mature organizations do not patch privacy holes; they build systems where privacy is an integral component of the architecture, resulting in more resilient and trustworthy products.

Discovery and Design: The Critical Foundation

This initial phase is the most critical for implementing Privacy by Design correctly. Decisions made here have cascading effects throughout the project. The cost of remediating a privacy flaw at this stage is orders of magnitude lower than attempting to fix it post-launch.

The primary objective is to map how personal data will flow through the proposed system. Key activities include:

- Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs): A PIA is a strategic tool, not a compliance exercise. Conducted before writing code, it identifies and mitigates potential privacy risks by forcing clarity on what data is being collected, why it is necessary, and how it will be protected.

- Data Flow Diagrams (DFDs): These visual maps trace the lifecycle of personal data, showing where it is collected, processed, stored, and shared with third-party services. DFDs make abstract data handling rules tangible for the entire team.

For instance, a DFD for a new analytics feature would illustrate user identifiers moving from the client application, through an API, to a processing service, and into a data warehouse. This immediately highlights potential vulnerabilities, such as unencrypted data in transit or excessive data retention.

Development and Architecture: Implementing Controls in Code

During development, architectural decisions are what make a privacy posture real. The engineering team translates design-phase requirements into robust, automated controls.

Technology choices are critical. Selecting a database with native column-level encryption or an authentication provider with built-in MFA strengthens controls from the start. The architecture must enforce principles like data minimization.

A common anti-pattern is building systems that collect a broad range of data “just in case” it might be useful later. This practice directly violates data minimization and creates an unnecessarily large risk surface. The architecture must enforce the collection of only what is strictly necessary for the feature to function.

Testing and QA: Verifying Protections

Privacy controls must be tested as rigorously as any other feature. The QA process must include specific test cases designed to validate that privacy measures function as intended and are resilient under stress.

The test plan should cover scenarios such as:

- Consent Withdrawal: Verify that when a user revokes consent, their data is programmatically excluded from relevant processing activities, such as marketing campaigns or analytics models.

- Data Deletion Requests: Test that a Data Subject Access Request (DSAR) for deletion purges user data completely from all systems, including primary databases, caches, logs, and third-party tools.

- Access Control Validation: Write tests to confirm that a user with one role cannot access data restricted to another. Can a standard user access an admin endpoint? Can one user view another user’s private data?

Deployment and Maintenance: Ongoing Vigilance

Privacy obligations do not end at deployment. The final stage of the SDLC requires continuous vigilance to ensure protections remain effective as the system evolves and new threats emerge.

This begins with secure configuration management during deployment—changing default credentials, closing unused ports, and hardening production environments. Once live, continuous monitoring is essential. Automated alerts should notify the team of potential privacy incidents, such as anomalous data access patterns or spikes in failed login attempts.

Finally, a well-documented process for handling data subject requests is critical. When a user requests their data or its deletion, the team must have a clear workflow to execute the request accurately and within legal timeframes. This process must be regularly tested and refined.

Architectural Patterns for Privacy by Design

Moving from principles to implementation requires selecting specific architectural patterns. These are the concrete engineering decisions that form the foundation of a private and secure system.

Getting these patterns right is what separates a truly resilient product from one with a superficial privacy policy.

Let’s examine the core patterns that enable privacy by design, including their real-world trade-offs.

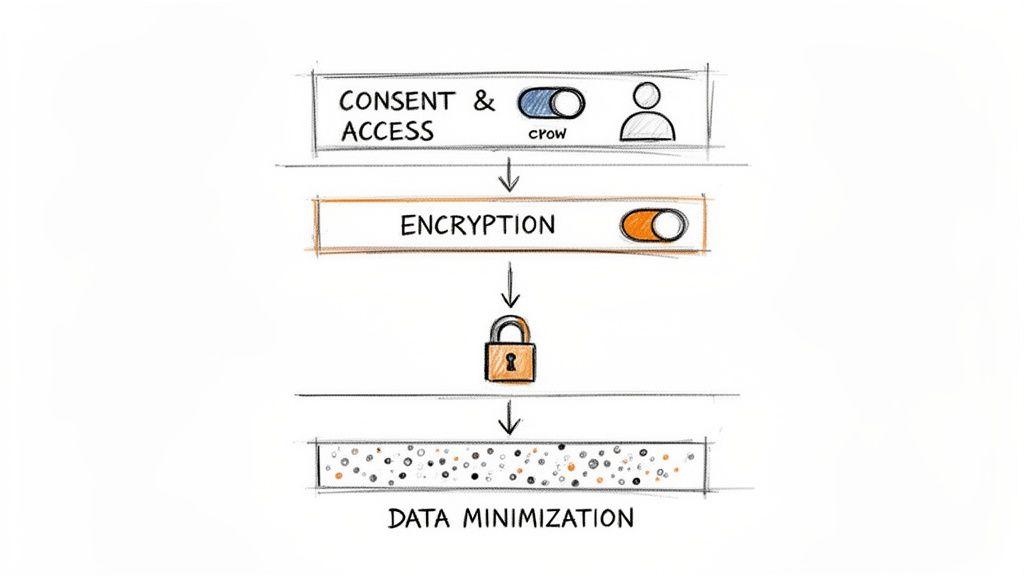

Data Minimization and Anonymization

The most effective way to protect data is not to collect it. Data minimization is an architectural discipline that requires justification for every data point collected and stored. It directly counters the high-risk practice of collecting data “just in case.”

When data collection is necessary, anonymization and pseudonymization are critical secondary controls. They break the link between data and an individual, enabling use cases like analytics while protecting privacy.

- Pseudonymization: Replaces direct identifiers (e.g., name, email) with a consistent but artificial token. This allows for user activity tracking without exposing direct personal information. The trade-off is reversibility: if the pseudonymization key is compromised, the data can be re-linked.

- Anonymization: Irreversibly removes or modifies data to make re-identification computationally infeasible. Techniques like k-anonymity ensure an individual is indistinguishable from at least k-1 others, while differential privacy adds statistical noise to query results to protect individual records.

The primary trade-off with anonymization is between data utility and privacy. Over-anonymizing can render data useless for analysis; under-anonymizing creates a false sense of security. The chosen technique must align with the data’s risk profile and intended use.

Research indicates that systems built with these principles report up to 60% fewer data breaches. A case study from a European hospital showed a 40% reduction in breaches over two years after embedding encryption and anonymization during a system redesign. This demonstrates that when privacy is integrated is as important as how. You can explore the full findings of this research on system design effectiveness.

Comparison of Data Anonymization Techniques

Selecting the right anonymization or pseudonymization technique requires understanding its strengths, weaknesses, and appropriate use cases. The following table compares common methods.

| Technique | Description | Best For | Key Trade-Off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudonymization | Replaces direct identifiers with consistent tokens or aliases. | Tracking user journeys or longitudinal analysis without storing PII directly. | Reversible. If the mapping key is compromised, data can be re-identified. |

| Data Masking | Obscures specific data fields by replacing them with fictional but realistic data. | Creating realistic test or development datasets from production data. | Can be complex to maintain realistic data structures and relationships. |

| K-Anonymity | Ensures an individual cannot be distinguished from at least k-1 other individuals in a dataset. | Publishing statistical datasets or sharing data with third parties for research. | Can reduce data utility, as some records may need to be suppressed or generalized. |

| Differential Privacy | Adds mathematical “noise” to query results to protect individual privacy. | Large-scale analytics and machine learning where individual privacy is paramount. | The added noise can affect the accuracy of queries on smaller datasets. |

No single technique is a complete solution. Robust systems often layer multiple approaches based on data sensitivity and its intended use, with the goal of making re-identification practically impossible while preserving necessary data utility.

Encryption in Transit and at Rest

Encryption is a non-negotiable, foundational control. It ensures that even if data is intercepted or storage is compromised, the information remains unreadable without the appropriate cryptographic keys. This protection must be applied universally.

Encryption in Transit protects data as it moves between services, such as from a user’s browser to your server or between internal microservices.

- Best Practice: Enforce modern TLS (Transport Layer Security), specifically TLS 1.2 or higher, across all public endpoints and internal APIs.

- Common Pitfall: A frequent mistake is terminating TLS at the network edge (e.g., a load balancer) and allowing unencrypted traffic within the “trusted” internal network. This creates a significant vulnerability if an attacker gains an internal foothold.

Encryption at Rest protects data stored in databases, object storage, or on backup media.

- Best Practice: Utilize transparent data encryption (TDE) offered by most modern databases (e.g., PostgreSQL, MySQL). For highly sensitive data, implement application-level encryption, where data is encrypted before being written to the database.

- Key Management: The security of encryption depends entirely on key management. Use a dedicated Key Management Service (KMS) like AWS KMS or HashiCorp Vault. Never hardcode encryption keys in application code or configuration files.

For guidance on structuring secure internal services, see our guide on Service-Oriented Architecture.

Robust Consent and Access Control

An architecture must be capable of enforcing the privacy promises made to users. This requires two key components: a robust consent management system and granular access controls based on the principle of least privilege.

A Consent Management Platform (CMP) is more than a cookie banner. Architecturally, it is a central service that records user choices for distinct data processing activities (e.g., marketing, analytics). All other services in the system must query the CMP before performing a relevant action.

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) is the standard pattern for enforcing least privilege. It ensures that users and systems can only access the data and perform the actions essential to their function.

- Implementation: Define clear roles with specific, minimal permissions (e.g.,

support_agent,billing_admin,user). - Granularity: Avoid overly broad roles. A support agent may need to view a customer’s ticket history but should not be able to access payment details unless it is critical for a specific, audited task. The architecture must support this level of fine-grained control.

Privacy Challenges in AI Systems

AI and machine learning introduce a new class of privacy risks that traditional software engineering practices do not fully address. Large Language Models (LLMs) are not simple databases; they learn, infer, and can memorize sensitive information in ways that are difficult to predict or control.

Applying privacy by design to AI requires a specialized approach.

While standard data protection methods are necessary, AI systems require additional layers of scrutiny. The nature of model training and inference creates unique vulnerabilities, from contaminated training data to models that inadvertently leak personal information.

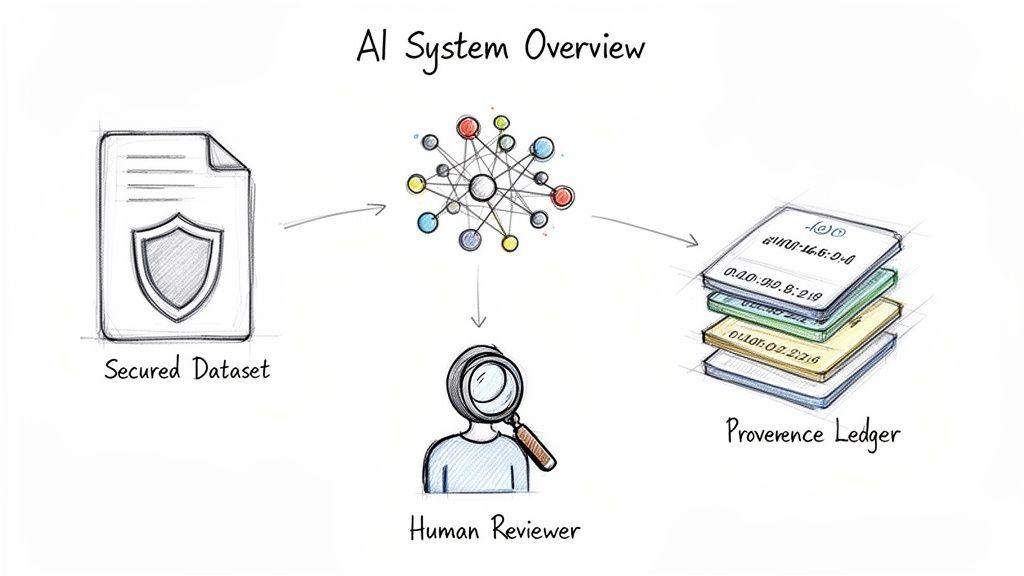

Data Provenance and Training Data Security

The integrity of an AI system depends on its training data. Without a verifiable record of data origin, legality, and transformations, the system is built on an unstable foundation. Data provenance is the discipline of maintaining a detailed, auditable log of a dataset’s lifecycle.

This is not a mere compliance exercise but a mitigation for serious technical risks. For example, a model trained on improperly sourced data may be vulnerable to model inversion attacks, where an adversary queries the model to reverse-engineer sensitive information from the training set.

A robust data foundation requires:

- Ethical Sourcing Audits: Verifying that data was collected with proper consent and for a legitimate purpose.

- Immutable Ledgers: Using technologies like blockchain or versioned object storage to create an unchangeable record of the data’s lifecycle.

- Strict Access Controls: Applying the principle of least privilege to training datasets, restricting access to authorized personnel and systems.

Without strong provenance, it is impossible to answer fundamental questions about a model’s behavior or biases, creating significant legal and reputational risk.

Privacy Risks in Embeddings and LLMs

A subtle yet serious risk in modern AI lies within the models themselves. LLMs can inadvertently memorize and reproduce personally identifiable information (PII) encountered during training. An innocuous query might trigger the model to reveal a name, address, or other private data.

This risk is amplified by embeddings—the numerical vectors models use to represent data. These vectors can unintentionally encode sensitive attributes, creating a backdoor for re-identification even if the raw data was sanitized.

A model does not need to store an exact email address to violate privacy. If its internal representations (embeddings) cluster individuals based on sensitive, inferred attributes like health status or financial distress, the potential for misuse is enormous. This is where privacy by design for AI becomes critical.

Mitigating these risks requires a multi-layered defense:

- Aggressive Data Sanitization: Before training, rigorously scrub datasets of all direct and indirect PII. This includes names, addresses, and any unique identifiers that could be combined for re-identification.

- Output Filtering and Guardrails: Implement a layer between the LLM and the user that scans model outputs for PII before they are displayed.

- Differential Privacy in Training: For high-risk applications, employ differential privacy techniques. These add statistical noise during training to make it mathematically infeasible for the model to memorize individual data points.

A structured approach is essential for teams building AI products. Use our free AI Risk & Privacy Checklist to evaluate your system’s architecture and identify specific vulnerabilities.

Human-in-the-Loop Governance

For high-stakes AI applications, full automation can be an unacceptable risk. When an AI makes decisions with significant human impact—in finance, healthcare, or legal domains—a Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) architecture is essential for safety, accountability, and trust.

HITL is a deliberate architectural pattern where the system is designed to defer to human judgment at critical junctures. This provides a vital safeguard against model errors and unintended consequences.

Architecturally, implementing HITL involves specific workflows:

- Confidence Thresholds: The model processes a request and calculates a confidence score. If the score falls below a predefined threshold, the case is automatically flagged for human review.

- Review Queues: Flagged cases are routed to a dedicated interface where a human expert can review the model’s input, its proposed output, and relevant context.

- Feedback Loop: The expert’s decision—approval, rejection, or modification—is logged and fed back into the system as training data to improve the model over time.

This approach integrates governance directly into the system’s functionality, turning a policy document into a living, operational process.

Establishing Governance and Measuring Success

Architectural patterns and lifecycle integrations are the engine of privacy by design, but governance provides the steering. Without clear ownership and metrics, even the best technical implementations can fail. Sustainable privacy requires a cultural shift supported by clear responsibilities and continuous verification.

This framework moves privacy from a series of isolated tasks to a core operational discipline, ensuring accountability is distributed throughout the organization.

Defining Roles and Responsibilities

Ambiguous ownership is a common failure mode. When everyone is responsible for privacy, no one is. A durable program requires clear role definitions.

- Data Protection Officer (DPO) or Privacy Lead: This role serves as the strategic hub, facilitating the process, providing expert guidance, and acting as the primary contact for regulators. This can be a fractional or external role for many organizations.

- Privacy Champions: These are engineers and product managers within development teams who receive additional training. They serve as the first line of defense, identifying potential privacy issues early and advocating for best practices in daily operations.

- Product and Engineering Leadership: The CTO and product leaders are ultimately accountable. They must allocate budget, enforce privacy gates in project approvals, and champion the business case for a strong privacy posture. A clear accountability framework is essential, as detailed in our practical guide to creating a code of conduct for engineering teams.

Continuous Verification Through Audits and Checklists

Governance must be an active, ongoing process. Mechanisms are needed to ensure privacy principles are followed in practice.

A Risk and Privacy Checklist integrated into a project management tool (e.g., Jira, Asana) is a pragmatic solution. Before a new feature can be marked “ready for development,” the product owner must complete the checklist, addressing questions such as:

- What new personal data does this feature collect?

- Has a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) been conducted?

- How is data minimization being applied?

- Are the new data flows documented and approved?

This gate forces a deliberate conversation about privacy before code is written. It should be paired with regular privacy audits—combining automated code scanning for vulnerabilities like hardcoded secrets with manual reviews of access control configurations.

The purpose of governance is not to create bureaucracy but to introduce productive friction. It forces a deliberate pause to consider privacy implications before they become exponentially more expensive to remediate.

Measuring What Matters

To demonstrate value and drive improvement, a privacy program must be measured. Leadership requires data that shows a return on investment.

Data highlights the stakes: 71% of consumers report they would stop doing business with a company if it shared sensitive data without permission. Regulators have levied over $4 billion in GDPR fines in the last three years, treating violations as serious corporate failures.

Key metrics to track include:

- Reduction in Privacy Incidents: Monitor the number of reported privacy-related bugs or security vulnerabilities on a quarterly basis.

- Data Subject Request (DSR) Response Time: Track the average time required to fulfill data access or deletion requests. A decreasing average indicates process efficiency gains.

- PIA Completion Rate: Measure the percentage of new projects that complete a Privacy Impact Assessment before development begins. This metric assesses process adherence.

These metrics transform privacy from an abstract ideal into a measurable component of operational excellence, proving its value to the entire business.

Common Questions About Privacy by Design

Even with a clear strategy, practical questions arise. Here are common queries from founders, CTOs, and product leaders adopting a privacy-first model.

Isn’t This Just GDPR Compliance?

No. GDPR compliance is a regulatory target, often addressed reactively. Privacy by Design is a proactive engineering philosophy that integrates data protection into the core of your systems from inception.

While PbD is a key component of GDPR (codified in Article 25), its goal is broader: to create systems that are fundamentally trustworthy and resilient, not merely compliant. A compliant system can still have architectural weaknesses; a system built with Privacy by Design is inherently more robust.

Is This Too Expensive for a Startup?

The upfront investment in planning and architecture is significantly less expensive than the long-term cost of inaction. Attempting to retrofit privacy controls into a live product is exponentially more costly and complex than building them in from the start.

A naive approach creates technical debt, operational disruptions, and potential data breaches, with costs that far exceed the initial investment. For a startup, building on a private foundation is a competitive advantage that fosters customer trust and avoids catastrophic fines or reputational damage.

The cost of a single urgent refactoring project to fix a post-launch privacy flaw will almost certainly outweigh the initial planning cost.

Will This Slow Down Our Development Velocity?

This is a common concern for agile teams. Initially, adopting practices like Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) and threat modeling requires a mindset shift and can add time to the discovery phase.

However, once these practices become routine, they cease to be a bottleneck. Over the long term, they often increase velocity by reducing security-related bugs, emergency patches, and the complex refactoring that halts development. The approach front-loads critical thinking to prevent expensive rework later.

What’s the First Practical Step We Can Take?

Begin with data minimization. It is the simplest and most effective initial action.

Before your next sprint planning session, challenge every new data point you intend to collect. Ask the team: “Do we absolutely need this data for the feature to function right now?”

This single question forces a critical conversation and begins to build the right habits. It requires no new tools or major process changes but immediately reduces your risk surface. It is the highest-leverage, lowest-cost starting point available.

Building secure, private, and maintainable software is at the core of what we do. At Devisia, we translate your business vision into reliable digital products and AI systems, with privacy as an architectural choice, not an afterthought. Learn more about our pragmatic approach to custom software development.